A 1971 New York Times article, “Decline and Decline of New York” by Roger Starr, shines a light on the drastic fall of the socio-cultural capital driving the city. More than five decades later, the Big Apple finds itself facing the same criticisms.

There’s an argument to be made about the net growth of a handful of the city’s industries, but when it comes to arts and culture, the aforementioned decline has become increasingly evident post-CoVid.

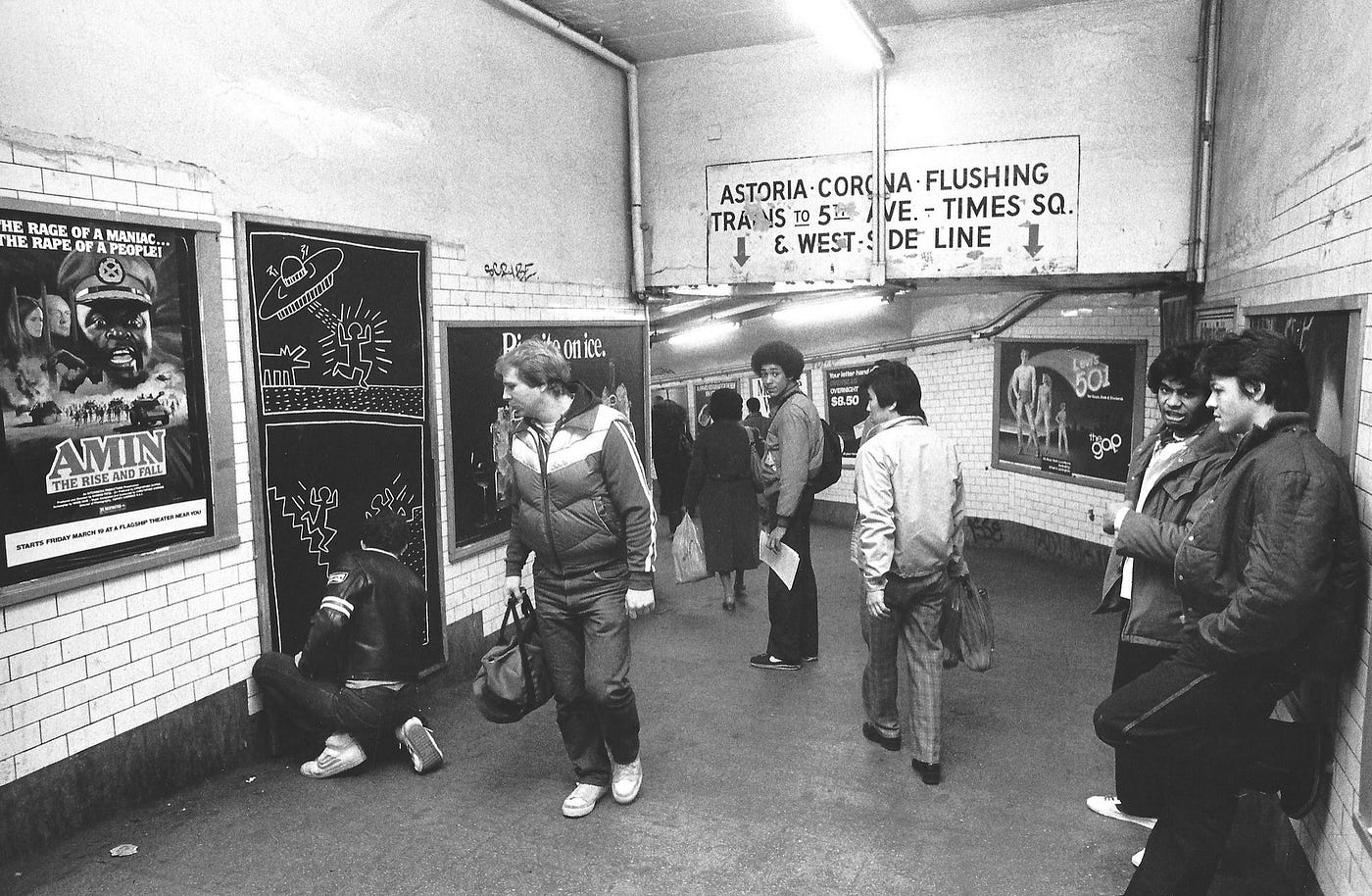

New York has been an artistic enclave in the United States, often referred to as a melting pot for cultures and cultural development. Its niche remains much needed in a relatively young country, not having had the time to develop established culture on a global scale. But the city’s rapid growth in the 1970s and 80s has given some consoling leeway to the US’ cultural enrichment process. Artistic movements like abstract expressionism and pop art were combined with a New York-inspired perspective, having an avalanche effect and propelling the city into its newfound identity.

These movements thrived in part because of a flow of migration to New York, but the real opportunity for artists was to create pieces that would be encapsulated in entire cultural movements.

The “struggling artist” is now losing its meaning in a city like New York, where the implications of living on low income are more grave than they have ever been. It’s hard to pinpoint when this dramatic shift happened, likely because it was slow and steady, with consumerist waves being inputs in this process of plunging the metropolis into what Kevin Baker of Harper’s Magazine calls an “urban crisis of affluence”. The current housing crisis is proof of what skyrocketing prices of living and poor provision of public goods can do to a city’s influx of professionals, especially those considered drivers of culture.

In May of 2010, Patti Smith told young artists that “New York has closed itself off to the young and struggling”. Her advice: “find a new city”.

Political wins like that of Assemblymember Zohran Mamdani, who unseated a long-time incumbent in Queens running on a housing-first, anti-gentrification, and anti-corporate landlord platform, signal a potential shift in how the city might reclaim its cultural future. Mamdani, a child of immigrants and a former housing counselor, won by mobilizing tenants, workers, and young creatives—many of whom have been directly affected by the affordability crisis that’s pushing artists and working-class people out of New York altogether. His victory wasn’t just electoral; it was symbolic of a larger refusal to accept the city’s transformation into a playground for real estate developers and finance capital.

While he has just won the Democratic primary and will face the general election in November, the win immensely reflects deep local support and momentum for his platform. The campaign imagined a version of New York that isn’t nostalgic or utopian, but possible: one where people can afford to stay, create, and shape the city’s culture from the ground up. In a city where gallery closures, studio displacements, and public arts budget cuts are the norm, Mamdani’s win offers a rare glimpse of resistance from within the political system; one that insists that cultural production and artistic survival are not luxuries, but rights tied to housing, labor, and dignity.

Starr’s argument about decline seemed reasonable 50 years ago, and made sense to New Yorkers who saw this happening first hand. What has happened since then was less expected, so it wouldn’t make sense to rule out revival. But sitting around and waiting for a cultural capital to revamp itself isn’t an option: artists still have to work, live, and create. Nordic European cities like Oslo and Copenhagen present themselves as leading candidates for young creatives, offering subsidies and social programs incentivizing artists to create with a purpose–all with good governance to thank for it.

Although these cities are increasingly positioning themselves as havens for artists, with strong public investment in culture and comprehensive social safety nets, New York still holds a symbolic and historical weight that’s hard to replicate. Its artistic empire, built on generations of migration, struggle, and reinvention, remains unmatched in its influence. But that empire cannot survive on legacy alone. The resurgence of grassroots political movements, like the one that propelled Mamdani into office, suggests that the fight for a livable, artist-friendly New York isn’t just a nostalgic fantasy, but a live political project. If the city is to remain a cultural capital, it must be reimagined not just by curators or developers, but by tenants, workers, and creatives organizing for the right to stay and shape its future. The question isn’t whether New York will fall—it’s whether enough people will fight for a version of it worth saving.

Leave a comment